9/11/2014 The Hollywood Reporter

The Brooklyn digital property’s CEO, Shane Smith, touts a $2.5B valuation and has lured backers from A&E to Fox by claiming magical access to young men. But his real trick might be marketing to a harder-to-reach audience: middle-aged media execs, writes Wolff

This story first appeared in the Sept. 19 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

Nancy Dubuc, Jeff Bewkes, James Murdoch, Tom Freston and Martin Sorrell are media executives cut from a similar button-down, corporate-culture cloth. So perhaps it is thrilling or titillating for them to meet someone like Vice’s Shane Smith, 44, who is all showman and promoter, a media type more reminiscent of the wild old days than the constrained new ones.

In late August, A&E Networks president and CEO Dubuc invested $250 million for a 10 percent interest in Vice, valuing the company at a whopping $2.5 billion (A&E is owned by Hearst and Disney). A tech venture firm, TCV, followed with $250 million for another 10 percent. Bewkes, Time Warner’s chairman and CEO, was set to do a deal with Vice at the beginning of the summer that would have valued the company at $2 billion — but Vice’s valuation rose more quickly than Bewkes’ ability to act. Murdoch bought 5 percent for $70 million in 2013 on behalf of 21st Century Fox and got a seat on the board; Sorrell, CEO of WPP, put $25 million in; and Freston, a former Viacom CEO, invested his own money early on and signed up as one of Vice’s key advisers. One might be forgiven for thinking of Zero Mostel in The Producers selling a Broadway show many times over.

In theory, these executives are drawn to Smith’s purported Pied Piper ability to attract that most sought-after and hard-to-reach (nearly always modified by “hard-to-reach”) demographic: distracted young men, more reliably playing video games than consuming traditional media. But they also are drawn to his Pied Piper ability to attract ever-more media executives and the ever-larger multiples they and their colleagues seem willing to pay for a piece of Vice.

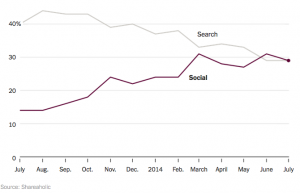

Arguably, the latter has been proved out much more completely than the former. These days one can attach many superlatives to Vice — it might be the hottest, savviest, coolest, richest, Brooklyn-est (according to Smith, it is the biggest employer in Williamsburg, the epicenter of Brooklyn-ness) new media company on the block — but one thing it does not necessarily have is a supersized audience. Vice makes a torrent of YouTube videos, but most, according to YouTube stats, have limited viewership. The New York Times, in its coverage of Vice’s TCV deal, seemed eager to believe in Vice and at the same time was perplexed by it, quoting the company’s monthly global audience claim of 150 million viewers but, as well, comScore’s more official and low-wattage number of 9.3 million monthly unique visitors. BuzzFeed, with an audience many times greater, has been valued at less than a third of Vice’s $2.5 billion.

That is, of course, part of Smith’s showman appeal. Even with his company’s obvious limitations — YouTube is an unreliable platform — he has boasted of producing a range of superhuman business-model breakthroughs.

It doesn’t much matter, for instance, that Vice has low audience numbers because it does not sell the usual CPM-based advertising. Instead, Smith sells high-priced sponsorships — marketing the Vice idea, in other words, rather than the Vice numbers. What’s more, playing coy, he does not seem to sell advertisers very much, often offering big consumer brands like Anheuser-Busch modest sponsorship credit at the ends of videos.

Then, too, Vice’s growing profits come in part because it continues to act like an outsider and pay young workers catch-as-catch-can alternative-media wages, even though it now is a richly funded enterprise.

Another of Vice’s accomplishments has been to position itself as a cutting-edge technology company rather than a media company, thereby achieving a techlike valuation. But Vice really has few tech skills beyond Final Cut Pro, running much more by old media seat-of-the-pants instincts and aggressive salesmanship than new digital algorithms. (Vice, with its many fledgling music writers looking for a byline, often is compared inexactly to BuzzFeed, with its ever-growing staff of engineers able to game the social-media world.)

Smith also, counterintuitively, has launched his company into the news business, making it a veritable Zelig of multiple international conflicts. Its tipping-point moment might have been Dennis Rodman‘s Vice-sponsored embrace of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il and its step into legitimacy with its earnest HBO world-report show. But this is at a moment when it never has been more difficult to monetize news programming. Indeed, so bizarre is the notion that Vice’s young-male audience will watch international news that puzzled media minds only can seem to conclude it must be true — and another epochal media disruption. (YouTube widely advertises Vice as a type of new-wave 60 Minutes.)

Smith earns, or claims to earn, serious money in foreign distribution, and over a lunch we shared not long ago in Brooklyn, he described that as his secret revenue generator, endlessly slicing and dicing and reselling low-cost video into hungry distant markets. This is an appealing and expansive view of the modern video world but a wholly unfamiliar and bewildering one to anyone in the licensing and rights business.

Vice, by most accounts, makes the major portion of its revenue (according to reports, as much as $500 million a year) functioning largely as an advertising agency or, even lower on the media value scale, a video production and event-planning house. Yet Smith has managed to position this service function as part of the new content revolution and Vice as a necessary link between brands and the creative world.

Even though many aspects of the Vice business model strain credulity, the illusion of having done the improbable is, it seems, especially welcomed by lots of people who ought to know better. This might be a sign of their confusion or, as well, because they would like to be hawking illusions themselves instead of having to manage media’s grimmer realities. Selling smoke is, of course, the media business at its most romantic and often most profitable.

Smith’s central premise, illusory or not, is that he has mastery of a certain audience, sensibility and zeitgeist zone — he has inserted Vice into the cultural consciousness. There is no real-life manifestation of this, no particular set of characters, nor memorable phrases, nor hit shows on which he can stand. Vice is not South Park, with its millions of young devotees over now-multiple generations, its cultural impact and its guaranteed cash flow.

Yet Vice has created an identity and a sensibility that people seem able to understand without having to experience. This perhaps is ideal for middle-aged chief marketing officers trying to reach the boy-man demo who don’t themselves want to vet the puerile. And broad-based brand identity arguably is a more valuable content asset than specific shows because you don’t have to pay expensive writers or need an actual hit.

Smith has built Vice against a background of enormous uncertainty and angst within the media business. His seeming effortlessness has made him the contrast gainer: He is fleet of foot, everyone else left standing by the side of the road. Vice and its multiplatform cultural targeting, many media people believe, is the most important example of the way forward in the media business.

But while Smith might be the avatar of the new — the quick, the cheap, the young, the cool, the digital — it turns out, reassuringly, that his way forward is television. What he wants most is a channel, a network, a place to call his own. His new investment capital is said to be earmarked for securing a cable platform, possibly one of the current A&E channels (in addition to A&E, Lifetime and History, A&E Networks operates seven lesser-known channels).

The outline of Smith’s prospective deal with Time Warner had TW selling CNN’s channel HLN (formerly Headline News) to Vice for a stake in the company (this is where the $2 billion valuation came from, which Vice then traded up to $2.5 billion). Curiously, it might have been to Vice’s advantage not to have done that deal, not only because its valuation climbed a further 25 percent in two months but also because having its own channel might have made it as accountable as everyone else. Vice might be a stronger brand for being hard to find — as something you think you should watch, rather than something you have decided not to watch.

Vice’s other trick, perhaps its central one, is not to have been taken over by a big company. None of its big media investors, all control freaks, is accustomed to a minority position — but somehow Smith has gotten them all to be willing and eager junior members of the Vice club. True, they all can look forward to the next deal and the next valuation bump. But largely they seem to have acquiesced to sideline status and to letting Smith call the shots because they really seem to believe he knows the secret, one he has yet to share with anyone. He’s got the magic — and nobody has seen magic in the media business for quite some time.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/michael-wolff-vice-media-why-731415