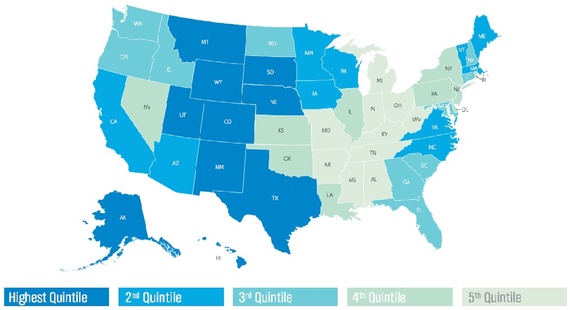

Years of state rankings have begun to paint a picture of an idyllic healthiest place to live.

Even if I remain unconvinced on that front, the fact that people manage to exercise more in Alaska than people in any other state—somehow—is just one of the many metrics that landed the state the number-one spot in a massive study of health and well-being across America, released this week.

Alaskans also reported the lowest stress levels of any population in the country over the past year, and the state had the lowest rate of diabetes. Maybe most surprisingly, despite the cold and darkness, Alaskans also had the second lowest rate of depression diagnoses in the country.

Witters, who oversaw the 2014 Gallup-Healthways study of 176,702 Americans, seemed to find genuine excitement in the ascension of Alaska—more than once calling it “really neat” and suggesting that it is a model that other states would do well to emulate. Indeed, the state’s victory is a realization of longer-term trends, Witters explained, that he has been measuring and observing in Alaska for a while now.

2014 Well-Being Rankings

These rankings have made little news in past years, in part because they are based entirely on self-reported surveys, which scientists are quick to dismiss. (Maybe Alaskans don’t actually exercise more; they’re just part of a statewide culture of lying about exercising. Maybe they don’t have diagnoses of depression because doctors aren’t recognizing symptoms, or people don’t feel comfortable talking about it in a telesurvey. Et cetera.) But seven years and 2.1 million surveys in, the longitudinal trends seem too substantial to dismiss outright. And if people are lying, Witters concedes, at least they are most likely lying in the same ways regularly.

Gallup’s methodology has been consistent for years, which lends some credence to trends. In the case of obesity, for example, national rates have been on the rise, from 25.5 percent of the population in 2008 to 27.7 percent in 2014. So that number may not be exact, but it is likely that the rate is indeed increasing.

In the Gallup index, people are scored in five categories, of which physical health is only one. There is also purpose (liking what they do each day, being motivated to achieve goals), social status (having supportive relationships and love in one’s life), financial status (having minimal economic stress), community (feeling safe, and having pride in one’s community).

And in community involvement, Alaska leads the nation, too. There, for example, the survey asks people whether they’ve received recognition in the last year for helping to improve their community. “That’s a tough nut to crack nationally,” Witters said. But among Alaskans, 28 percent say they have—which is actually the best rate in the country. They are also, despite (because of?) the bear population, fifth in the country in terms of feeling safe and secure.

“Another really good one that I love about Alaska, within the purpose element, is learning something new and interesting every day,” Witters explained, “which is an important psychological need.” That metric is a reason that college towns tend to score highly on the well-being index. And there, too, Alaska is number one in the nation, with 72 percent of residents feeling daily intellectual stimulation.

“Kentucky and West Virginia are really in bad shape,” said Witters. There diagnoses of depression are perennially among the highest in the nation, as are stress levels and high blood pressure. Nearly a third of West Virginians smoke tobacco, compared to 19 percent of people nationwide.

Behind those disheartening numbers is another particularly important metric: having someone in your life who encourages you to be healthy. There West Virginia also ranks last in the country. “That is a really good leverage point that they could take advantage of, that cultural change of encouraging accountability to one another,” said Witters, when I asked them how West Virginia could learn from Alaska. “It’s about having someone who has fundamental expectations of you, in how you live your life.”

Even for all their shortcomings, these rankings are fodder for growth and improvement, and they only stand to become more so. In places, the index is already being used by policy makers and businesses, with an eye to bringing programming and investment to their states. In Iowa, for example, governor Terry Branstad boasted on his website in 2013 when Iowa moved from number 16 to number nine, taking that as evidence of success in his Healthiest State Initiative. The program is actually predicated entirely on the Gallup well-being rankings, explicitly aiming to take Iowa to the top spot by 2016.

Apart from seeking glory or avoiding shaming, motivation for improvement can also come from bald financial arguments. These well-being factors are interdependent, but also influence healthcare spending, notes Janet Calhoun, a senior vice president at Healthways. She frequently invokes the rejoinder that communities with high well-being scores spend less money on healthcare, and their people are more productive overall. The argument, then, is that there can be significant regional economic return when communities invest in improving the wellbeing of a population. And similarly in the private sector, Calhoun said, “When employers invest in improving the well-being of their work force, they have a healthier bottom line for their business.”

“These metrics don’t move a lot if you’re not addressing them,” Witters said. “Until there are statewide initiatives that are meant to address these basic problems in places like Kentucky and West Virginia, they’re going to be stuck at the bottom.”

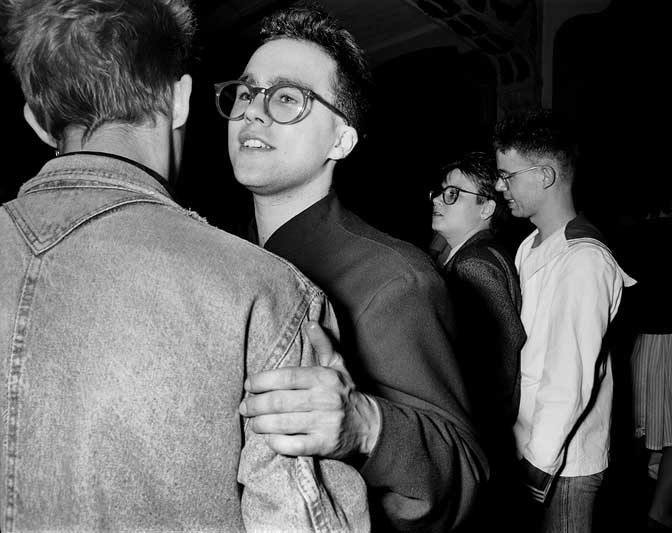

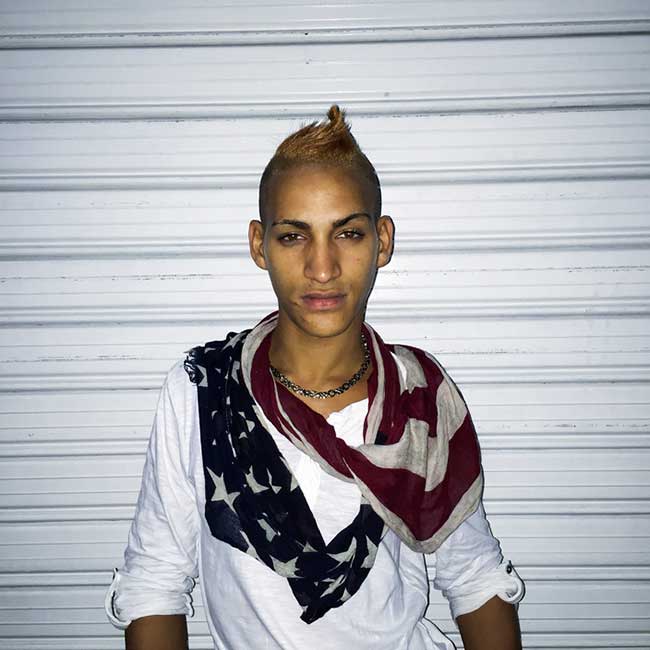

This is a picture of me and my family when I was 9. My parents still claim that they had no idea I was gay. They’re sweet.

This is a picture of me and my family when I was 9. My parents still claim that they had no idea I was gay. They’re sweet.