A slow-moving bureaucracy. An antiquated business model. A horde of upstart competitors. Can National Public Radio survive?

Animations by Lisa Larson-Walker. Images via Flickr CC.

One day in May 2015, Eric Nuzum stood before a gathering of influential NPR trustees and board members, and showed them a photograph of a young woman with shoulder-length brown hair. “This is Lara,” Nuzum’s slide read. “Lara is the future of NPR.”

“NPR’s mission must be to serve that woman the way we served her parents,” Nuzum remembers saying. “Nothing else matters.”

At the time, Nuzum was NPR’s head of programming. The presentation, which he delivered at a meeting of the NPR Foundation, was meant to drive home his most closely held belief about public radio: that young people have different habits, expectations, and aesthetic inclinations than the millions of loyal listeners NPR has been serving since its birth in 1971. “Lara” was a stand-in for an audience that NPR was failing to attract—according to one analysis, the median age of NPR’s radio audience has steadily climbed from roughly 45 years old two decades ago to 54 last year—and one it would need to reach in order to guarantee its survival.

What Nuzum didn’t say during his presentation was that, one day earlier, he had decided to end his decade-long career at NPR and sign a contract with the Amazon-owned audiobook company Audible. Nuzum’s job there would be to develop a slate of original programming that would give Audible a stake in the tantalizing new market for audio storytelling. Although the NPR Foundation people didn’t know it yet, the man who was warning them about needing to win over Lara had just been stolen away by a corporate audio giant.

Today, Nuzum belongs to a club you could call the NPR apostates—onetime servants of public radio who parted ways with the organization and entered the private sector amid frustrations over how NPR and its member stations were approaching the future of the industry. In addition to Nuzum—whose Audible project launched in beta last week—other prominent members include Alex Blumberg, who founded the podcasting startup Gimlet Media, and Adam Davidson, who is an investor in Gimlet and an adviser to a new digital audio unit at the New York Times.

(Slate is also home to some NPR alums who have made the leap into private sector digital audio, including Andy Bowers and Steve Lickteig, who work at Panoply, The Slate Group’s audio business, as well as Mike Pesca, who left NPR’s New York bureau to start a daily Slate podcast called The Gist.)

The work these defectors are doing outside of NPR—and the ways in which it promises to destabilize their old employer—has, in recent weeks, become the subject of intense and emotional debate in the world of public radio. The tumult was touched off in late March, when an NPR executive announced that the network’s own digital offerings—most importantly, its marquee iPhone app, NPR One—were not to be promoted during shows airing on terrestrial radio.

The ban was widely viewed as proof that NPR is less interested in reaching young listeners than in placating the managers of local member stations, who pay handsome fees to broadcast NPR shows and tend to react with suspicion when NPR promotes its efforts to distribute those shows digitally. After the gag order was made public, dozens of public radio and podcasting people set about picking at an old scab—discussing, spiritedly, in multiple forums, whether the antiquated economic arrangements that govern NPR’s relationships with its member stations are holding it back from innovation.

The debate also raised an even thornier and as-yet-unanswered question: What is the value of NPR’s core journalistic offerings—the brief, sober dispatches that air every day on its flagship shows Morning Edition and All Things Considered—in an age when its terrestrial audience is growing older and younger listeners seem to prefer addictive, irreverent, and entertaining podcasts over the news?

The critics say NPR has been standing with its toes in the ocean for too long, curbing its digital ambitions in order to appease legacy radio stations. As its competitors dash into the waves, the question of whether NPR can ever catch up, and what will become of it if it doesn’t, has become increasingly urgent. Can the people who are running NPR make radio for Lara? Or has she already tuned them out for good?

* * *

To understand NPR’s predicament, it’s crucial to first understand what NPR is and what NPR is not. In some ways, the second part is easier. NPR is not a radio station, and it is not responsible for every show in which polite voices speak in a restrained, earnest manner about the issues of the day; other players that traffic in such fare include American Public Media, which produces Marketplace, and Public Radio International, which co-produces The Takeaway. NPR is not involved in the making ofThis American Life, a program that was launched by member station WBEZ in Chicago and has been operating independently since 2015.* Nor did NPR create Serial, the blockbuster podcast that debuted a little less than two years ago and convinced many people that there is money to be made in the medium of podcasting.

So what is NPR? In short, it’s a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., that produces and distributes an assortment of popular radio shows to federally funded local stations all across the country. Some of these stations are tiny and depend entirely on programming they have licensed from outside entities. Others, such as New York’s WNYC or Boston’s WBUR, are powerhouses that produce nationally syndicated shows of their own, like WNYC’s Radiolab and WBUR’s On Point With Tom Ashbrook.

What does this have to do with whether or not NPR will still be making journalism that people want to listen to in 50 years? The answer lies in NPR’s flagship news programs: Morning Edition, which typically airs on member stations from 5 a.m. to 9 a.m. ET, and All Things Considered, which comes on at 4 p.m. and continues through drive time. The two programs, which are known inside NPR as “the newsmagazines,” are the biggest shows NPR produces, both in terms of revenue and audience. Broadcast on approximately 900 radio stations across the country, they reach an estimated weekly audience of more than 25 million people.

Between the licensing fees that member stations pay to air the shows and the sponsorship revenue they attract, Morning Edition and All Things Considered are responsible for bringing in a bigger slice of NPR’s annual budget than any other source of funding. Member stations—which have controlled a majority of NPR’s board seats since the early 1980s—have strongly opposed the idea of making the shows available as on-demand podcasts, fearing a loss of listeners and revenue. According to critics like Davidson and Nuzum, limitations like these have prevented NPR from making a bigger impact in the digital space.

The way the newsmagazines work journalistically is fairly straightforward, with NPR’s reporters filing pieces to their desk editors, who work closely with the shows’ producers and hosts in deciding what will go on the air. Some of the stories come from NPR’s 17 foreign bureaus; others are produced by the 98 reporters the network has stationed across the United States. Ultimately, the newsmagazines end up airing a few dozen of these stories per day, along with host interviews with newsmakers and NPR correspondents (Steve Inskeep interviewing Nina Totenberg about a recent Supreme Court decision, say), local news patched in by member stations, and live hourly news briefings that hurtle through the day’s headlines in five minutes or less.

By their nature, the newsmagazines are “perishable,” meaning they are designed to be listened to when they are fresh. In sensibility, they have been impressively consistent for decades, and longtime listeners have come to count on them for succinct updates on important world events, measured analysis of major national stories, evocative slice-of-life reporting from around the country, as well as occasional offbeat pieces that are delivered by NPR correspondents with a reliably mature sense of playfulness.

The NPR News voice, though not monolithic, is unmistakably distinct from the diverse range of audio programming that has taken off in the recent podcast boom. Some of the shows that are part of that wave, such as Red Bull Studios’ Bodega Boys, BuzzFeed’sAnother Round, and Slate’s own political and cultural talk shows, have found a market as “low-touch” productions, which require little in the way of reporting (by the hosts) or audio engineering (by producers) and rely mostly on the podcasters’ charisma, expertise, and chemistry. Other successful podcasts, such as Reply All, Criminal, andYou Must Remember This, have paved the way for something else entirely: meticulously crafted feature journalism that, in Alex Blumberg’s words, feels less like a collection of radio segments and more like “narrative-driven, textured, sound-rich documentaries.”

The conventional wisdom among podcasters like Blumberg is that, in 2016, listeners want audio programming that makes them feel as though they’re getting to know a person or a topic intimately, whether through the familiar banter of beloved panelists or through lovingly produced works of storytelling. Whereas the parents of the elusive Lara turned to NPR because they wanted someone trustworthy to tell them the news, younger generations seem to find satisfaction in the velvety bedroom voice of 99% Invisible host Roman Mars as he murmurs about furniture and the self-consciousness of Serial’s Sarah Koenig, who makes the method of her reporting part of her story.

NPR News reporters usually can’t get that personal, in part because, as Gimlet’s Adam Davidson puts it, they are in the impossible position of having to simultaneously “appeal to 80-year-olds in Alabama and 20-year-olds in Brooklyn.”

“All evidence suggests that with on-demand audio, people don’t want the three-to-four-minute radio stories,” Davidson told me. “They don’t want the anecdotal lede, followed by an expert saying something. They want something longer. More engaged. Something that isn’t designed for 30 million people in mind, but 1 million people who are more like them. They want something looser, more fun.”

Ironically, looser and more fun is a good way to describe what NPR was like when it first came on the air in the 1970s. As Steve Oney describes in his forthcoming history of NPR, American Air, National Public Radio was hatched by “misfits, castoffs, and dreamers” out of a desire to experiment with audio, and was widely viewed as the province of left-wingers and hippies. The first broadcast, emblematically, was a chaotic, 25-minute portrait in three acts of the massive anti-war rally that shook Washington, D.C., on May 3, 1971; in Oney’s words, the unusual piece rang out with “a vibration from a realm where youthful earnestness commingled with merry-prankster lunacy, land-grant university idealism, New England pragmatism, and a native instinct for storytelling.”

Jay Allison, who filed stories to All Things Considered in its early days and is now something of a public radio elder statesman, said doing work for NPR back then was about “discovering the world with this new technological marvel, which was portable tape.” Allison, who now hosts PRX’s The Moth Radio Hour, said he sometimes misses NPR’s more freewheeling days. When he turns on All Things Considered in 2016, he said, “There’s hardly any commentary, and very little exploratory or strange portraiture, documentary, or poetic stuff.”

“By abandoning that kind of sonic terrain of exploratory narrative,” Allison said, “NPR has ceded that territory to the podcasters.”

* * *

As NPR’s critics see it, letting others dominate that terrain will ultimately prove fatal, because it’s where young listeners now live. But for the moment, NPR’s top executives, including CEO Jarl Mohn, are unapologetically focused on shoring up the radio audience for Morning Edition and All Things Considered instead of diverting newsroom resources to begin industrial-scale podcast production.

But Mohn is adamant that NPR has not let its focus on the newsmagazines distract from its podcasting efforts. The network already has a bunch of successful podcasts, Mohn told me, including a pair of talk shows (the NPR Politics Podcast and the Pop Culture Happy Hour) and an ornate science show, Invisibilia, which in its second season will consist of seven episodes created over the course of many months by a team of three.

“The mythology is that somehow we’re being left behind,” Mohn said. “Now, the thing that I find so laughable about the argument is, if you look at the iTunes chart any given week … we’re consistently four of the Top 10 podcasts, and consistently six of the Top 20. No one else has the number of hit podcasts that we have. No one.”

Still, when it comes to allocating resources, NPR’s current leadership is proceeding cautiously. According to Anya Grundmann, who replaced Eric Nuzum at NPR as the head of programming,Morning Edition and All Things Considered are simply too important to the economics of the network to be anything other than the top priority. “We need to make sure that we are continuing to invest in the newsmagazines,” she said. “If we pulled 50 people from the newsroom to do podcasts, that would be a challenge.”

It isn’t just about the bottom line, though. Mohn and his team seem to genuinely believe that NPR’s formidable network of reporters—as well as the local journalists working at member stations—will allow the organization to prevail over the private podcast shops growling at their gates.

“Look, your storytelling is great,” Mohn said. “It’s fine. It’s fun. It’s interesting. It’s charming. But we’re covering Syria. We’re covering Ebola.”

The CEO is not the only one drawing attention to NPR’s status as a mighty news organization—and suggesting that, so far at least, its profit-minded competitors have behaved more like purveyors of entertainment than of news.

In a Facebook post written in response to a recent jeremiad by Adam Davidson describing public radio’s dire prospects, the reporter Lourdes Garcia-Navarro—who is currently based in Brazil and previously reported from Libya on the Arab Spring—drew a sharp contrast between what she and her colleagues do and what Davidson did on the first episode of his new Gimlet podcast Surprisingly Awesome, which promises listeners “Stories about things that sound totally boring, but turn out to be totally awesome”:

[S]eriously, NPR does matter unless you want to live in a world with ONLY 30 minutes of vocal fry on the value and meaning of Mold (which is GREAT) and not, also, let’s say … news of a terror attack in Belgium. I’m sorry if that seems quaint to you.

This distinction between “news” and podcast-style “storytelling” has emerged as a key fault line in the debate over NPR’s future. And while it is considered impolite to value one above the other, there’s a tendency among some podcast people to think of themselves as too ambitious and creative for the constraints of the four-minute radio news spot, and a tendency among some radio people to look askance at the pretentions of podcasters and their twee, personality-driven soundscapes.

“It’s an art form and they do a really good job at it,” said JJ Sutherland, a former war reporter and producer for NPR who left in 2012. “I saw myself more as a journalist than someone creating art. And that’s not to disparage anyone who does it differently, but I spent from 2004 to the end of 2011 going back and forth from Iraq. And you know what? I didn’t do it because it was fun.”

Of course, fun is not necessarily the enemy of seriousness, and to their credit, podcasters have proven that even very complicated and abstract material can be made compelling with the right touch. Planet Money, the twice-weekly podcast about the economy that Davidson and Blumberg founded as an experiment at NPR in 2008, provides perhaps the best illustration of this: On the show’s de-facto pilot, “The Giant Pool of Money,” which aired on This American Life, Blumberg and Davidson managed to explain the financial crisis to delighted listeners over the course of an hourlong episode that was no less edifying for being deliriously entertaining as well.

If free-form storytelling can make even credit default swaps engaging, Blumberg and Davidson thought at the time, it could work on anything. In the wake of the rapturous reception that Planet Money received from NPR listeners, its creators started asking themselves why a four-minute news brief should still be considered the ideal vehicle for reporting on and explaining current events. If people are getting more out of the longer, more propulsive stuff, why wouldn’t the NPR newsroom try to produce more of it?

“The 3-4 minute story should not be the core audio product of NPR,” Davidson said in an email. “It shouldn’t be the thing that NPR’s reporters and editors spend most of their days focused on. I know from experience that it takes different muscles, different tools to do longer-form stories. I think it would be smart if NPR had more of its staff spending a decent chunk of their time working on developing those skills and muscles.”

Blumberg and Davidson ultimately left NPR out of frustration with what they saw as the organization’s half-hearted embrace of a concept they felt they’d proved. Since Mohn became CEO in 2014, there has been a further exodus of high-level, digitally minded talent, including Kinsey Wilson, who was pushed out as chief content officer and is now spearheading an all new digital audio unit at the New York Times; Margaret Low Smith, an NPR lifer who was running the news division at the time of her departure; executive editor Madhulika Sikka; director of vertical initiatives Matt Thompson; and content strategy executive Sarah Lumbard.*

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t people still at NPR who are trying to push the organization to be more adventurous and experimental: Despite the departures, there remains a clutch of public radio optimists at NPR News who are operating from the premise that their core product must change if they want to still have an audience after their existing listeners are no longer around.

Two people in particular are leading the charge: Kelly McEvers, who took over as a co-host of All Things Considered last year as part of an effort to make the show appeal to a younger audience, and Sara Sarasohn, who oversees content for an app called NPR One, which many in public radio consider to be the most exciting thing to have happened at NPR in years.

McEvers and Sarasohn are trying to bring NPR into the audio present from different angles. McEvers is tackling the problem of what the news should sound like, both onAll Things Considered and in podcast form, with her new show Embedded. On ATC, she told me, she’s been striving to talk the way she does when she’s talking to her friends. “I’m trying to make myself sound a little less like an anchor might have in the past—a little more conversational and transparent,” she said. Though some older listeners, including McEvers’ parents, have not been entirely supportive of her decision to start saying “like” and “you know” on the air, the less buttoned-up tone might turn out to be more inviting to young ears.

With Embedded, McEvers has created a show that is textured and process-driven, likeSerial, and one that’s being promoted as a demonstration of what NPR can do when it challenges its newsroom to make high-end documentary programming. McEvers, who reported from the Middle East for years before joining All Things Considered, uses each episode to take her listeners along on a reporting trip, burrowing down into one story and feeling around in it at a leisurely pace. For the first episode, which appeared on iTunes on March 31, McEvers spent a week with a group of painkiller addicts in Indiana whose insistence on sharing needles had caused a local HIV epidemic. Over the course of the 30-minute episode, McEvers lets us listen in as addicts inject themselves and murmur answers to her questions. As McEvers narrates her reporting, we learn in great detail about how the people she encountered fell into their habits and gain a visceral appreciation for the difficulty of getting clean.

Embedded may or may not turn out to be a cultural phenomenon. But NPR wants as many people as possible to hear it, which is where Sara Sarasohn and the NPR One app comes in. Though marketed as a “Pandora for public radio,” NPR One is better understood as a high-stakes experiment in creating a dedicated audience for all of NPR’s offerings—digital and terrestrial. Whereas the previous NPR News app required listeners to make playlists of segments they wanted to hear, NPR ONE generates a streaming playlist of audio content based on a person’s interests and feedback. In one session you could be taken from a Morning Edition dispatch on police reform in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to an All Things Considered segment on the Federal Reserve to an episode of the Pop Culture Happy Hour. There are offerings from other networks too—if you’re a fan of Reveal, the podcast from the Center for Investigative Reporting, you can tell the app you want it in your mix, and decide when it comes up whether you want to listen to it or skip.

I’ve been using NPR One for about three weeks, and I have found it extremely enjoyable. Some days, when the algorithm is really humming, it makes me wish my commute to work was longer; on other days, when I’m tired and walking the dog, I turn it on for no other reason than to spare myself the trouble of actively choosing something to listen to.

But the app isn’t just a delight for listeners. It also generates precise data for NPR about when people skip segments and what keeps them engaged. This data, Sarasohn told me, has been used to train NPR hosts and reporters on how to write copy that is most likely to catch listeners’ ears. (One lesson Sarasohn has learned: Instead of opening with the who/what/where/when/why of a traditional news story, open with a “big idea” sentence that explains the stakes right away.)

On the strength of these efforts—not to mention the slate of podcasts that Mohn boasted of when we spoke—it is reasonable to conclude that progress is being made at NPR, and that when the organization does put its weight behind something new and bold, it is more than capable of competing with its new challengers. WhenEmbedded hit the top of the iTunes podcast chart, NPR’s head of news Michael Oreskes tweeted at Adam Davidson, “May I ask you fine innovators a question, respectfully? If @NPR is so strategically inept, why is Embedded #1 today?”

Davidson and his ilk, however, worry these steps are too little, too late. In their view, NPR should have rushed the field sooner and staked out a dominant position in digital audio back when it had the sector almost entirely to itself. Instead, its leadership abetted the rise of small, swift competitors with whom they must now contend for market share and talent, all while trying to accommodate the interests of terrestrial member stations—many of which still fill their weekend slots with zombielike reruns of Car Talk—in order to maintain an anachronistic business model.

A big part of the problem, several former NPR staffers say, is that some of the most creative producers and reporters in the newsroom are too often thwarted when they move to pursue new ideas—not because they are always told no by their superiors, but because the process of getting something made at the organization tends to be grindingly bureaucratic and incremental, and requires feats of strength, patience, and political finesse on the part of those who try.

Perhaps the best evidence of this tendency is a long-gestating podcast from the Code Switch team, which was formed three years ago to cover race. Though the official line at NPR is that the team wasn’t ready to have a podcast until recently—it is now being piloted and will debut “soon,” according to a spokeswoman—if NPR had moved faster to develop the project, they might already have a major franchise on their hands. Instead, the Code Switch staff have been limited to appearing on other people’s podcasts, publishing written pieces for their vertical on NPR.org, and contributing the occasional news segment to Morning Edition or All Things Considered.

* * *

There is something quaint about the idea of turning on a radio to learn about the day’s events. We are, after all, bombarded by news constantly—on our computers, on our phones, on TV, from newspapers, from cable news networks, from our friends on social media. Against that backdrop, it seems like there’s a very real possibility that the medium in which NPR’s reporters work—not just terrestrial radio, but audio full stop—could simply lose its place as a news source in people’s lives.

And yet, one of the discoveries Sara Sarasohn has made from NPR One is that listeners skip over newscasts less frequently than they skip over anything else. Maybe that’s because there remains something valuable about hearing someone reliable offer you a summary of every important thing that’s happened in the world since the last time you checked. That experience—of being passively informed and temporarily relieved of the responsibility to decide what is and isn’t worth knowing—still seems to hold great appeal. Perhaps, in our on-demand world, that appeal is even stronger. As Sarasohn put it to me, the need to know that “the world is still turning” is not going away.

For now, NPR, with its unrivaled audio newsroom, still has a head start in the race to fill that need. Even its most acerbic critics would agree on that. Every day, though, that advantage shrinks, as companies like Audible and the New York Times step into the digital audio fray with heightened ambitions and the resources to realize them.

NPR should take the threat seriously. They still have a chance to win Lara over. But she won’t wait around forever.

*Correction, April 11, 2016: This article originally misstated that NPR’s former chief content officer Kinsey Wilson was hired by the New York Times to spearhead its new digital audio unit. Wilson was initially brought on by the Times as an editor for strategy and innovation, and is now executive vice president for product and technology. (Return.)

*Correction, April 13, 2016: This article originally misstated the year when This American Life began operating independently. It was 2015, not 2014. (Return.)

That’s a whole different kettle of fish.

That’s a whole different kettle of fish.

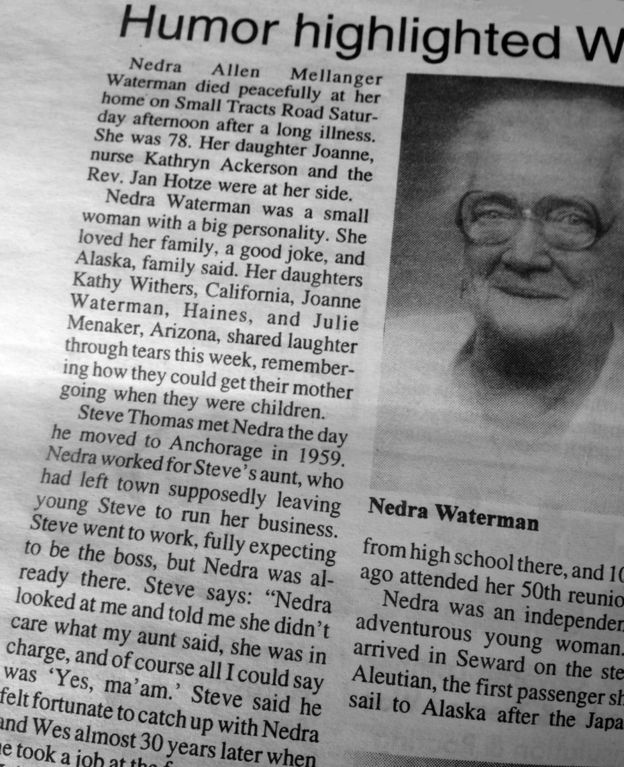

Nedra Waterman with her husband Wes – she died in 1997

Nedra Waterman with her husband Wes – she died in 1997

Rene Pisel Walker and her husband David

Rene Pisel Walker and her husband David Olen Nash died at sea in 1999

Olen Nash died at sea in 1999 Olen’s mother Becky Nash working on a quilt

Olen’s mother Becky Nash working on a quilt

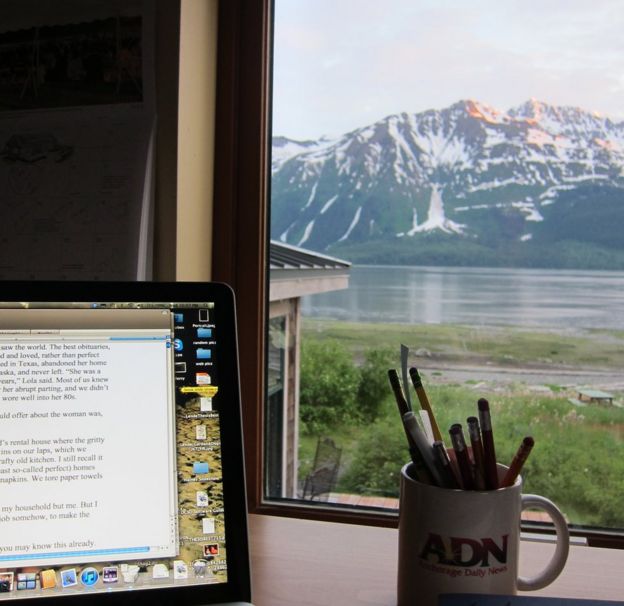

The desk where Lende writes obituaries

The desk where Lende writes obituaries