One night in early January, a little after 9 o’clock, a dozen Netflix employees gathered in the cavernous Palazzo ballroom of the Venetian in Las Vegas. They had come to rehearse an announcement the company would be making the next morning at the Consumer Electronics Show, the tech industry’s gigantic annual conference. For the previous year, Netflix had been plotting secretly to expand the availability of its streaming entertainment service, then accessible in about 60 countries, to most of the rest of the world. Up to this point, Netflix had been entering one or two countries at a time, to lots of fanfare. Now it was going to move into 130 new countries all at once, including major markets like Russia, India and South Korea. (The only significant holdout, for now, was China, where the company says it is still “exploring potential partnerships.”) Netflix executives saw this as a significant step toward the future they have long imagined for the company, a supremacy in home entertainment akin to what Facebook enjoys in social media, Uber in urban transportation or Amazon in online retailing.

Ted Sarandos, who runs Netflix’s Hollywood operation and makes the company’s deals with networks and studios, was up first to rehearse his lines. “Pilots, the fall season, summer repeats, live ratings” — all hallmarks of traditional television — were falling away because of Netflix, he boasted. Unlike a network, which needs shows that are ratings “home runs” to maximize viewers and hence ad dollars, he continued, Netflix also values “singles” and “doubles” that appeal to narrower segments of subscribers. Its ability to analyze vast amounts of data about its customers’ viewing preferences helped it decide what content to buy and how much to pay for it.

Sarandos can be an outspoken, even gleeful, critic of network practices in his zeal to promote what Netflix views as its superior model — on-demand and commercial-free streaming, on any device. That glee was on full display in these remarks. For years, he said, “consumers have been at the mercy of others when it comes to television. The shows and movies they want to watch are subject to business models they do not understand and do not care about. All they know is frustration.” That, he added, “is the insight Netflix is built on.”

When Sarandos was done, Reed Hastings, Netflix’s chairman and chief executive, took the stage. A pencil-thin man, he seemed swallowed up by the empty ballroom. He squinted uncomfortably under the lights. He and a number of other Netflix executives had spent the morning at a meeting in Laguna, Calif., where a rare torrential rainstorm grounded air traffic, forcing them to make the five-hour drive to Las Vegas. They arrived only a few hours earlier. To make matters worse, Hastings was feeling ill.

Haggard and tired, he stumbled irritably through his presentation. But as he neared the finale, Hastings broke out into a small, satisfied smile. “While you have been listening to me talk,” he said, reading from a monitor, “the Netflix service has gone live in nearly every country in the world but China, where we also hope to be in the future.” Even though this was only a practice run — and even though it would be a long time before anyone knew whether global expansion would pay off — the Netflix executives sitting in the ballroom let out a loud, sustained cheer.

They had good reason to celebrate. Netflix, since its streaming service debuted in 2007, has had its annual revenue grow sixfold, to $6.8 billion from $1.2 billion. More than 81 million subscribers pay Netflix $8 to $12 a month, and slowly but unmistakably these consumers are giving up cable for internet television: Over the last five years, cable has lost 6.7 million subscribers; more than a quarter of millennials (70 percent of whom use streaming services) report having never subscribed to cable in their lives. Those still paying for cable television were watching less of it. In 2015, for instance, television viewing time was down 3 percent; and 50 percent of that drop was directly attributable to Netflix, according to a study by MoffettNathanson, an investment firm that tracks the media business.

All of this has made Netflix a Wall Street favorite, with a stock price that rose 134 percent last year. Easy access to capital has allowed the company to bid aggressively on content for its service. This year Netflix will spend $5 billion, nearly three times what HBO spends, on content, which includes what it licenses, shows like AMC’s “Better Call Saul,” and original series like “House of Cards.” Its dozens of original shows (more than 600 hours of original programming are planned for this year) often receive as much critical acclaim and popular buzz as anything available on cable. Having invented the binge-streaming phenomenon when it became the first company to put a show’s entire season online at once, it then secured a place in the popular culture: “Netflix and chill.”

But the assembled executives also had reason to worry. Just because Netflix had essentially created this new world of internet TV was no guarantee that it could continue to dominate it. Hulu, a streaming service jointly owned by 21st Century Fox, Disney and NBC Universal, had become more assertive in licensing and developing shows, vying with Netflix for deals. And there was other competition as well: small companies like Vimeo and giants like Amazon, an aggressive buyer of original series. Even the networks, which long considered Netflix an ally, had begun to fight back by developing their own streaming apps. Last fall, Time Warner hinted that it was considering withholding its shows from Netflix and other streaming services for a longer period. John Landgraf, the chief executive of the FX networks — and one of the company’s fiercest critics — told a reporter a few months ago, “I look at Netflix as a company that’s trying to take over the world.”

At the moment, Netflix has a negative cash flow of almost $1 billion; it regularly needs to go to the debt market to replenish its coffers. Its $6.8 billion in revenue last year pales in comparison to the $28 billion or so at media giants like Time Warner and 21st Century Fox. And for all the original shows Netflix has underwritten, it remains dependent on the very networks that fear its potential to destroy their longtime business model in the way that internet competitors undermined the newspaper and music industries. Now that so many entertainment companies see it as an existential threat, the question is whether Netflix can continue to thrive in the new TV universe that it has brought into being.

To hear Reed Hastings explain it, there was never any doubt in his mind that, as he told me during one interview, “all TV will move to the internet, and linear TV will cease to be relevant over the next 20 years, like fixed-line telephones.” Viewers, in other words, will no longer sit and watch a show when a network dictates. According to Hastings, Netflix may have begun as a DVD rental company — remember those red envelopes? — but he always assumed that it would one day deliver TV shows and movies through the internet, allowing customers to watch them whenever they wanted.

Now that future has begun to take shape. The television industry last went through this sort of turbulence in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when cable television was maturing. Previously, of course, television had been mostly transmitted via the public airwaves, and the major networks made the bulk of their money from advertising. But cable provided an indisputably better picture, and the proliferation of cable networks came to offer a much greater variety of programming. In time, consumers concluded that it was worth paying for something — TV — that had previously been free. This meant that in addition to advertising dollars, each cable channel received revenue from all cable customers, even those who didn’t watch that channel. By 2000, 68.5 million Americans had subscriptions, giving them access to the several hundred channels the industry took to calling “the cable bundle.”

Hastings knew the internet would eventually compete with that bundle, but he wasn’t entirely sure how. And so he had to be flexible. Sarandos says that in 1999, Hastings thought shows would be downloaded rather than streamed. At another point, Netflix created a dedicated device through which to access its content, only to decide that adapting its service to everything from mobile phones to TV sets made more sense. (The Netflix device was spun out into its own company, Roku.) In 2007, even as Netflix’s DVD-by-mail business remained lucrative, and long before the internet was ready to deliver a streaming movie without fits and starts, Hastings directed Netflix to build a stand-alone streaming service.

Netflix’s approach to what it streams has been similarly flexible. At first, the company focused on movies, logically enough: 80 percent of its DVD rentals were films. But despite deals with two premium movie channels, Starz and Epix, Netflix found the distribution system to be largely inhospitable. Netflix usually didn’t get access to a new movie until a year or so after it ran in theaters. It then held the distribution rights for only 12 to 18 months; eventually, the movie went to free TV for the next seven or eight years. This frustrated customers who couldn’t understand why something was there one month and gone the next or why, for that matter, so many titles were missing entirely from Netflix’s catalog.

So the company shifted to television. Cable networks like FX and AMC were developing expensive, talked-about dramas, the kind HBO pioneered with “The Sopranos” and “The Wire.” But these series, with their complex, season-long story arcs and hourlong format, seemed to be poor candidates for syndication, unlike self-contained, half-hour sitcoms like “Seinfeld,” which can be watched out of order.

Hastings and Sarandos realized that Netflix could become, in effect, the syndicator for these hourlong dramas: “We found an inefficiency,” is how Hastings describes this insight. One of the first such series to appear on Netflix was AMC’s “Mad Men,” which became available on the site in 2011, between its fourth and fifth seasons. Knowing from its DVD experience that customers often rented a full season of “The Sopranos” in one go, Netflix put the entire first four seasons of “Mad Men” online at once. Bingeing took off.

Television networks lined up to license their shows to Netflix, failing to see the threat it posed to the established order. “It’s a bit like ‘Is the Albanian Army going to take over the world?’ ” Jeff Bewkes, the chief executive of Time Warner, famously joked back in 2010. The occasional voice warned that Netflix would become too big for the industry to control, but mostly the legacy media companies viewed the fees from Netflix as found money. “Streaming video on-demand” rights, as they were called, hadn’t even existed before Netflix asked to pay for them. And because the networks didn’t understand how valuable those rights would become, Netflix got them for very little money.

Everyone seemed to be a winner, including the shows themselves. In 2012, for instance, Netflix began streaming the first three seasons of “Breaking Bad,” the dark drama produced by Sony that ran on AMC. Though praised by critics, “Breaking Bad” had not yet found its audience.

“When the folks at Sony said we were going to be on Netflix, I didn’t really know what that meant,” Vince Gilligan, the creator of “Breaking Bad,” told me. “I knew Netflix was a company that sent you DVDs in the mail. I didn’t even know what streaming was.” Gilligan quickly found out. “It really kicked our viewership into high gear,” he says. As Michael Nathanson, an analyst at MoffettNathanson, put it to me: “ ‘Breaking Bad’ was 10 times more popular once it started streaming on Netflix.”

This was around the time that network executives started to recognize the threat that Netflix could eventually constitute to them. “Five years ago,” says Richard Greenfield, a media and technology analyst at BTIG who happens to be Netflix’s most vocal proponent on Wall Street, “we wrote a piece saying that the networks shouldn’t license to Netflix because they were going to unleash a monster that would undermine their business.” That’s exactly what seemed to be happening.

Worse, they realized that Netflix didn’t have to play by the same rules they did. It didn’t care when people watched the shows it licensed. It had no vested interest in preserving the cable bundle. On the contrary, the more consumers who “cut the cord,” the better for Netflix. It didn’t have billions of legacy profits to protect.

Yet the networks couldn’t walk away from the company either. Many of them needed licensing fees from Netflix to make up for the revenue they were losing as traditional viewership shrank. Negotiations between a network or a studio and Netflix became fraught, as the networks, understanding the value of their streaming rights, sought much higher fees. In some cases, those negotiations broke down. The Starz deal, for example, was not renewed after it ended in 2012. (Chris Albrecht, the chief executive of Starz, would later describe the original deal as “terrible.”)

This was also the moment that Netflix started to plot its move into original programming. In 2012, Sarandos began to argue internally that to stand apart from the crowd, and to avoid being at the networks’ mercy, Netflix needed exclusive content that it fully controlled. “If we were going to start having to fend for ourselves in content,” Sarandos says, “we had better start exercising that muscle now.” In short, Netflix needed to begin buying its own shows.

“We could see that eventually AMC was going to be able to do its own on-demand streaming,” Hastings says. “Or FX. We knew there was no long-term business in being a rerun company, just as we knew there was no long-term business in being a DVD-rental company.”

Still, Hastings was cautious. Producing original material is a very different business from licensing someone else’s shows. New content requires hefty upfront costs — one show alone would most likely cost more than the $30 million a year Netflix reportedly once paid Starz for its entire library of movies. Developing its own series would thrust it into the unfamiliar business of engaging with producers, directors and stars. Back in 2006, the company set up a way to distribute independent films, called Red Envelope Entertainment, but it failed, and Hastings shut it down. (“We would have been better off spending the money on DVDs,” he told me.) Now it was going to give original content another try — with much higher stakes.

Sarandos had a show he was itching to buy: “House of Cards,” a political drama that was being pitched by David Fincher, the well-known director, and would star Kevin Spacey. Sarandos knew that, according to Netflix’s vast database, many of the company’s subscribers liked the kind of drama that Fincher and Spacey wanted to make. But algorithms alone weren’t the deciding factor. He and Hastings figured that Fincher, who directed films like “Fight Club” and “The Social Network,” would create a critical and popular sensation.

In any case, Sarandos said, the potential reward vastly outweighed whatever financial and reputational risk “House of Cards” represented. “If it is a flop, we will have overpaid for one series,” he told Hastings. “But if it succeeds, we will have changed the brand.”

In winning over Fincher, Sarandos faced two other obstacles: a competing offer from HBO, which also wanted “House of Cards,” and the fact that no one had ever made a show for a streaming service before. For decades, when movies went straight to video without a theater run, they were ipso facto failures in Hollywood’s view; for a seasoned director like Fincher, picking Netflix presented the same risk of marginalization. Sarandos overcame both by offering freedom and money. “There are a thousand reasons for you not to do this with Netflix,” he told Fincher. “But if you go with us, we’ll commit to two seasons with no pilot and no interference.” Sarandos also offered Fincher a reported $100 million for 26 episodes, at the high end for an hourlong drama.

The first season of “House of Cards” became available in February 2013. It was an immediate hit with viewers and critics. Five months later, Netflix posted the first season of “Orange Is the New Black,” which Sarandos had ordered before “House of Cards” went into production. Critics lavished praise on the new show as well. Having begun its life as a Silicon Valley tech company, Netflix had somewhat improbably become a television network.

Reed Hastings doesn’t have an office. “My office is my phone,” he says. “I found I was rarely using my cubicle, and I just had no need for it. It is better for me to be meeting people all around the building.” On the several occasions I interviewed him at the company’s headquarters in Los Gatos, Calif., we met in the cafeteria. Although Netflix employees describe him as an intense, blunt boss, Hastings comes across in public as relaxed and undefensive. He spent our interviews leaning back in his chair, his arms folded and legs crossed, tossing off answers to my questions as if it were a day at the beach.

Born and raised in the Boston suburbs — his great-grandfather was the wealthy investor Alfred Lee Loomis, who played a critical role in the invention of radar — Hastings, now 55, is one of those tech executives who came to California to attend Stanford (grad school for computer science in his case) and never left. The tech company he ran before Netflix was called Pure Software, which made debugging tools for software engineers. Before Netflix, Hastings had no experience in the entertainment industry.

Although news coverage now tends to focus on its shows, Netflix remains every bit as much an engineering company as it is a content company. There is a reason that its shows rarely suffer from streaming glitches, even though, at peak times, they can sometimes account for 37 percent of internet traffic: in 2011 Netflix engineers set up their own content-delivery network, with servers in more than 1,000 locations. Its user interface is relentlessly tested and tweaked to make it more appealing to users. Netflix has the ability to track what people watch, at what time of day, whether they watch all the way through or stop after 10 minutes. Netflix uses “personalization” algorithms to put shows in front of its subscribers that are likely to appeal to them. Nathanson, the analyst, says: “They are a tech company. Their strength is that they have a really good product.”

It is no surprise that Hastings, given his engineering background, believes that data, above all else, yields answers — and the bigger the data set, the better. “The worst thing you can do at Netflix is say that you showed it to 12 people in a focus room and they loved it,” says Todd Yellin, the company’s vice president of product innovation. He likes to note that customers will at most consider only 40 to 50 shows or movies before deciding what to watch, which makes it crucial that the company puts just the right 50 titles on each subscriber’s screen. (All the data Netflix collects and dissects can yield surprising correlations: For example, viewers who like “House of Cards” also often like the FX comedy “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.”)

There is another underappreciated aspect of Netflix that Hastings views as a competitive advantage: what he calls its “high performance” culture. The company seeks out and rewards star performers while unapologetically pushing out the rest.

A meeting at Netflix headquarters in Los Gatos, Calif. Credit Peter Earl McCollough for The New York Times

One person who helped Hastings create that culture is a woman named Patty McCord. The former head of human resources at Pure Software, she was also Hastings’s neighbor in Santa Cruz. She car-pooled to work with him and socialized with his family on weekends. “I thought the idea for Netflix was kind of stupid,” she told me. But she trusted Hastings’s instincts and wanted to keep working with him. Her title was chief talent officer.

The origins of the Netflix culture date to October 2001. The internet bubble burst the year before, and Netflix, once flush with venture capital, was running out of money. Netflix had to lay off roughly 50 employees, shrinking the staff by a third. “It was Reed’s first layoffs,” McCord says. “It was painful.”

The remaining 100 or so employees, despite working harder than before, enjoyed their jobs more. McCord and Hastings concluded that the reason was that they had held onto the self-motivated employees who assumed responsibility naturally. Office politics virtually disappeared; nobody had the time or the patience. “There was unusual clarity,” McCord says. “It was our survival. It was either make this work or we’re dead.” McCord says Hastings told her, “This is what a great company feels like.”

As luck would have it, the DVD business took off right around the time of the layoffs. By May 2002, Netflix was doing well enough to go public, selling 5.5 million shares at $15 a share. With the $82.5 million Netflix reaped from the offering, Hastings started hiring aggressively again. This time, he and McCord focused on hiring “fully formed adults,” in their words, go-getters who put the company’s interests ahead of their own egos, showed initiative without being asked and embraced accountability. Dissent and argument were encouraged, even demanded.

For those who fit in, Netflix was a great place to work — empowering and rational. There are no performance reviews, no limits on vacation time or maternity leave in the first year and a one-sentence expense policy: Do what is in the company’s best interest. But those who could not adapt found that their tenure at Netflix was stressful and short-lived. There was pressure on newcomers to show that they had what it took to make it at Netflix; those who didn’t were let go. “Reed would say, ‘Why are we coming up with performance plans for people who are not going to work out?’ ” McCord says. Instead, Netflix simply wrote them a check and parted ways.

McCord also convinced Hastings that he should ask himself a few times a year whether he would hire the same person in the same job if it opened up that day. If the answer was no, Netflix would write a larger check and let the employee go. “If you are going to insist on high performance,” McCord says, “then you have to get rid of the notion of retention. You’ll have to fire some really nice, hard-working people. But you have to do it with dignity.

“I held the hands of people weeping, saying, ‘I want to be here forever,’ ” McCord says. “I would tell them, ‘Nothing lasts forever.’ I would say to Reed, ‘I love them, too, but it is our job to be sure that we always have the right people.’ ”

In 2004, the culture was codified enough for Netflix to put it on a sequence of slides, which it posted on its corporate website five years later. It is an extraordinary document, 124 slides in all, covering everything from its salaries (it pays employees what it believes a competitor trying to poach them would) to why it rejects “brilliant jerks” (“cost to effective teamwork is too high”). The key concept is summed up in the 23rd slide. “We’re a team, not a family,” it reads. “Netflix leaders hire, develop and cut smartly, so we have stars in every position.”

After Hastings, the executive I spent the most time with at Netflix was Yellin, a former independent filmmaker who joined the company in early 2006, when he was in his early 40s. Yellin quickly distinguished himself by pushing back hard whenever he thought Hastings was wrong about something. “There was a culture of questioning, but I pushed the envelope,” he says. He also helped develop a style of meeting that I’d never seen before. At the one I sat in on, there were maybe 50 people in a small circular room with three tiers of seats, like a tiny coliseum, allowing everyone to easily see everyone else. The issue at hand seemed pretty small to me: They were discussing whether montages on the opening screen of the user interface would be more effective in keeping subscribers than still images or trailers. But the intensity of the discussion made it clear that the group took the matter very seriously. Various hypotheses had been tested by sending out montages to 100,000 or so subscribers and comparing the results with another 100,000 who got, say, still images. (This is classic A/B testing, as it’s known.) Every person present had something to say, but while there were strong disagreements, no one’s feathers seemed ruffled.

One of my last interviews at Netflix was with Tawni Cranz, the company’s current chief talent officer, who started under Patty McCord in 2007. Five years later, McCord, her mentor, left. When I asked her why, she visibly flinched. She wouldn’t explain, but I learned later that Hastings had let her go.

It happened in 2011, after he made his biggest mistake as chief executive. He split Netflix into two companies — one to manage the DVD business and the other to focus on streaming. Customers were outraged; for many, the move meant a 60 percent price increase if they kept both the DVD and the streaming service. With complaints mounting and subscribers canceling, Hastings quickly reversed course and apologized. In the three weeks following this episode, the price of Netflix shares dropped 45 percent, and Wall Street questioned the company’s acumen. Hastings decided to re-evaluate everyone in the executive ranks, using the litmus test McCord taught him: Would he hire them again today? One of the people this led him to push out was McCord.

One analyst said, ‘Once people start watching shows that don’t have commercials, they never want to go back.’

“It made me sad,” she said when I called to ask her about it. “I had been working with Reed for 20 years.” Netflix had just given the go-ahead to “House of Cards,” and McCord said she “didn’t want to walk away in the middle of the next thing.”

But she also felt a sense of pride. She was gratified that Hastings had taken her advice so thoroughly to heart.

Bill Murray, wearing a tuxedo with no tie, stepped out of a black car and meandered through a throng of people toward Ted Sarandos. It was a crisp night in December, and Murray had just arrived at the New York premiere of “A Very Murray Christmas,” a loosely structured, thinly plotted musical-comedy special directed by Sofia Coppola and including guest appearances by George Clooney, Chris Rock, Michael Cera and others. In the fall of 2014, when Coppola and Murray first cooked up the idea, they went straight to Sarandos. By then, a year and a half after “House of Cards” became available, Netflix had a reputation for deep pockets, marketing savvy and a hands-off policy with the “talent.” The idea of doing away with a pilot, born of desperation when Sarandos was wooing Fincher, had now become Netflix’s standard practice, much to the delight of producers and directors.

“Ted,” Murray said, as they shook hands warmly, “you should get a promotion.” He grabbed Sarandos by the lapels, pulled him close and added loudly, “You are the future!” The two men laughed uproariously.

From the time he arrived at Netflix in 2000, Sarandos has had the final say on both Netflix’s licensing deals and its original programming. An Arizona native, Sarandos was working for a large video-retail chain when Hastings hired him to negotiate DVD deals directly with the studios. Sarandos had been in love with movies all his life: He worked his way through college by managing an independent video store. If he had chosen a different path, it’s easy to imagine him having become a traditional Hollywood executive instead of an industry antagonist.

When the networks complain about Netflix, Sarandos is the one who usually shoots back. Netflix doesn’t publish ratings! Ratings, he says, are irrelevant to Netflix because the only number that matters is subscriber growth; Netflix doesn’t need to aggregate viewers for advertisers, and it doesn’t care when consumers watch their shows, whether it’s the day they are released or two years later. Netflix spends too much money for its shows! “Big Data helps us gauge potential audience size better than others,” Sarandos told me.

At an investment conference late last year, David Zaslav, the chief executive of Discovery Communications, which operates the Discovery Channel, articulated the case for having networks rethink their relationship with Netflix. Streaming video-on-demand platforms “only exist because of our content,” Zaslav said, in an obvious reference to Netflix. “To the extent that our content doesn’t exist on their platforms — not to be too pejorative — they are dumb pipes. We as an industry are supporting economic models that don’t make sense.”

Sarandos, who had spoken earlier in the day, had clearly anticipated the criticism: “Zaslav says that we built a great business on their content,” he said. “That’s just not true. We did not renew their deal when they wanted a premium. So we replaced it with other programming that got us just as many viewers for less money.”

Those who think Netflix will come to dominate television have a simple rationale: Netflix has exposed, and taken advantage of, the limitations of conventional TV. The more time people spend on Netflix — it’s now up to nearly two hours a day — the less they watch network television. “Our thesis is that bingeing drives more bingeing,” says Greenfield, the Wall Street analyst. “Once people start watching shows that don’t have commercials, they never want to go back. Waiting week after week for the next episode of a favorite show,” he says, “is not a good experience for consumers anymore.”

Still, despite the rise in Netflix’s share price over the past few years, the company has no shortage of doubters on Wall Street. Some distrust Netflix’s numbers, arguing that millions of people no longer watch the service anymore but keep their subscriptions because they are so inexpensive. Netflix has announced that it will raise prices this year, and the Netflix skeptics believe the price increase will cause subscribers to cancel in droves. Other critics note the slowdown in the growth of domestic subscribers, by far the company’s most profitable segment. In addition, Netflix, between its content costs and the cost of adding subscribers, is spending more than it collects in revenue. How long can that continue?

Finally, the pessimists point out that Netflix makes very little profit: In the first quarter of this year, for instance, Netflix had nearly $2 billion in revenue but only $28 million in profit. Despite the significant moves by Netflix into original programming, Wall Street still values Netflix more like a platform company — a business that uses the internet to match buyers and sellers, like Uber — than a content company, like a studio or a network. Its valuation is currently $5 billion more than Sony, for example. Hastings, who has been very blunt about the company’s strategy of plowing money back into the business, has promised bigger profits sometime in 2017. Whether he can deliver on that promise will be a significant test of investors’ faith in him.

Todd Yellin, the vice president of product, says, “The worst thing you can do at Netflix is say that you showed it to 12 people in a focus room and they loved it.” Credit Peter Earl McCollough for The New York Times

One of the most prominent Netflix skeptics is Michael Pachter, a research analyst at Wedbush Securities, a Los Angeles-based investment bank. In his view, Netflix’s true advantage in the beginning was that it had the entire game to itself, and the networks, not realizing how valuable streaming rights would be, practically gave them away. He had a “buy” on the stock from 2007 to 2010, he told me. But, he added, referring to those years when Netflix had streaming all to itself, “If it’s too good to be true, then it will attract competition.”

Now, he said, the networks and studios are charging higher fees for their shows, forcing up Netflix’s costs. Netflix doesn’t own most of the shows that it buys or commissions, like “House of Cards,” so it has to pay more when it renews a popular show. In addition to the money it now spends on content, it also has more than $12 billion in future obligations for shows it has ordered. The only way it can pay for all of that is to continue adding subscribers and raise subscription rates. And even then, Pachter says, the networks will extract a piece of any extra revenue Netflix generates. “It is naïve to think that Netflix can raise its price by $2 a month and keep all the upside,” he said. “I defy you to look at any form of content where the distributor raises prices and the supplier doesn’t get more. That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard.

“Netflix,” Pachter concluded, “is caught in an arms race they invented.” He compared Netflix to a rat racing on a wheel, staying ahead only by going faster and faster and spending more and more: As its costs continue to go up, it needs to constantly generate more subscribers to stay ahead of others.

And if that doesn’t happen? If subscriber growth were to stall, for instance, then Wall Street would stop treating it as a growth stock, and its price would start falling. Slower growth would also increase the cost of taking on more debt to pay for its shows. The company would be forced to either raise subscription prices even higher or cut back on those content costs or do both, which could slow subscriber growth even further. Netflix’s virtuous circle — subscriber growth and content expenditures driving each other — would become a vicious circle instead.

Five years from now, will the networks have taken the steps they need to prevent Netflix from dominating television? Will they have improved their technology, withdrawn most of their shows from Netflix or embraced streaming without sacrificing too much of their current profits? Or is Netflix in the process of “disintermediating” them, offering consumers such an improved viewing experience that the networks will instead be pushed to the sidelines?

Matthew Ball, a strategist for Otter Media, who writes often about the future of television, thinks the latter is more likely. He says that today, when you have a cable subscription, you have access to hundreds of channels — in effect, they all share you as a customer. The cable bundle puts you in a television ecosystem, and you flip from one show to the other depending on what you want to watch. In the emerging on-demand world, television won’t work that way: All the networks will have their own streaming service and customers will have to pay a fee for every one. The days when networks could make money from people who never watch their shows will end.

One consequence is that networks will have to have one-on-one relationships with their viewers — something they have little experience with, and which Netflix, with its ability to “personalize” its interactions with its 81 million customers, has mastered. Another consequence is that as streaming becomes the primary way people watch television, they are highly unlikely to pay for more than a small handful of subscription-TV networks. What they will want, Ball believes, is a different setup: companies that offer far more programming than any one network can provide. Netflix, clearly, has already created that kind of ecosystem. “Netflix is ABC, it is Discovery, it is AMC, it is USA and all the other networks,” Ball said. “Its subscribers don’t say, ‘I love Netflix for Westerns, but I’ll go somewhere else for sci-fi.’ The old model just doesn’t work in an on-demand world.”

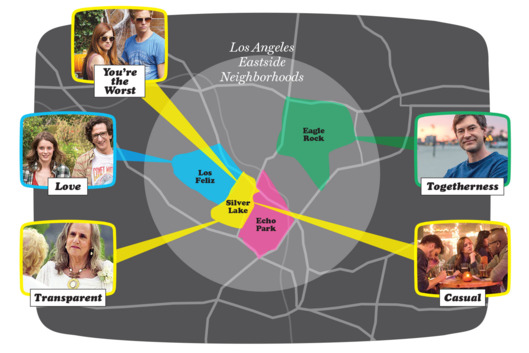

In this vision of the future, Netflix’s most potent competitor is likely to be Amazon, which is also developing an extensive array of content, including many of its own original shows. Early on, it, too, produced a highly praised series, “Transparent.” It, too, has no allegiance to the cable bundle. And it has the kind of revenue — exceeding $100 billion — that neither the networks nor Netflix can approach. Compared to the networks, Netflix may have an imposing war chest, but in a fight with Amazon, it would be outgunned.

According to Ball, what Netflix is counting on to maintain its primacy and to start making big profits is “unprecedented scale.” That’s where the effort to create a global network, the one that was announced in January at the Consumer Electronics Show, comes in. In April, when the company announced its first-quarter results, it said it had added 4.5 million international subscribers. Yet success, and profits, are still some way off, as Hastings is the first to acknowledge.

YouTube, he notes, is available in more than 50 languages; Netflix can be seen in only 20 languages. Netflix was primarily attracting people in its new countries who speak English as it races to “localize” its service in each country. Netflix is ordering shows with an international flavor, like “Narcos,” but so far it has only a handful up and running. Netflix wants to make “the best Bollywood movie that’s ever been produced,” Hastings told an Indian publication; it wants to make Japanese anime; it wants to make local films for every market; it wants global rights when it licenses shows — something that, once again, contravenes Hollywood’s conventional business model, in which rights are sold on a country-by-country basis. The company still has much to learn about each country’s quirks and tastes and customs, and it will be a while before it can hope to earn a profit from its global customers.

To my surprise, Hastings spoke to me about the current moment as a “period of stability.” It took me a while to understand what he meant, given how unstable the television industry seems to be right now. But Netflix has spent much of its existence zigging and zagging, responding to the pressures of the marketplace.

“When we were in the DVD business,” Hastings said, “it was hard to see how we would get to streaming.” Then it was hard to see how to go from a domestic company to a global one. And how to go from a company that licensed shows to one that had its own original shows. Now it knew exactly where it was going. “Our challenges are execution challenges,” he told me.

Asked what the competitive landscape would look like five years in the future, he returned to the analogy he used earlier with the evolution of the telephone. Landlines had been losing out to mobile phones for the past 15 years, he said, but it had been a gradual process. The same, he believed, would be true of television.

“There won’t be a dramatic tipping point,” he said. “What you will see is that the bundle gets used less and less.” For now, even as Hulu and Amazon were emerging as rivals, he claimed that the true competition was still for users’ time: not just the time they spent watching cable but the time they spent reading books, attending concerts.

And Hastings was aware that even after the bundle is vanquished, the disruption of his industry will be far from complete. “Prospective threats?” he mused when I asked him about all the competition. “Movies and television could become like opera and novels, because there are so many other forms of entertainment. Someday, movies and TV shows will be historic relics. But that might not be for another 100 years.”

Joe Nocera is the sports-business columnist for The New York Times.