Filmography:

Love Creator, Executive Producer 2016 – 2017

Brooklyn Nine-Nine Executive Story Editor 2013 – 2014

Awkward. Story Editor 2013

Girls Staff Writer 2012

Agent: Larry Salz (UTA)

Management: Circle of Confusion

Legal: Lev Ginsburg (Ginsburg Daniels)

In the Media:

Lesley Arfin on Love, Selfishness, and the Art of Oversharing | New York Magazine | February 24, 2016

Sitting in the cluttered Los Feliz apartment that writer Lesley Arfin shares with her husband, comedian-writer Paul Rust, I feel as if I’ve stepped through a TV screen and into the living-room-interior set of Love, the new Netflix series the couple co-created, and found the show’s fictional universe rolling confessionally along.

Love, which premiered February 19, was co–executive produced by Judd Apatow and tells the fitful story of how L.A. 30-somethings Gus (Rust) and Mickey (Gillian Jacobs) become a couple. It’s not all just meet-cute. The episodes are 30-minute deconstructions of modern courtship, with all the detours and dysfunction that occurs when two maladjusted people try to achieve some kind of intimacy.

“Mickey and Gus are based on Paul and me,” the 36-year-old Arfin explains, sitting on a green corduroy couch. “Well, versions of us.” The genesis of the show came from questions Arfin had been asking herself about her relationship: “I’d said to Paul, ‘I know I love you, and it’s like, why? It’s not just, You’re my soul mate.’ ”

Excavating that “why” is a preoccupation of both the show’s and Arfin’s, and the blurry line between where her fictional characters end and her personal life begins is even blurrier here at home. As Arfin is talking, Claudia O’Doherty, the Australian comic who plays Mickey’s roommate on the show, pops down the stairs, trying on dresses for her friend’s approval.

Arfin, a former writer on Girls, had been looking to tackle the subject of post-infatuation love. “What does it look like when there is no romance anymore and we’re on the couch in our sweats? Because I didn’t know. I was figuring out how people got together and stayed together.”

Armed with that idea, Arfin and Rust, who married last October, began outlining a film script, which they took to Apatow. He liked the idea but envisioned a TV show that followed a relationship from the outset rather than picking up in the middle. After some light coaxing, Arfin and Rust went along with the change. “I can be stubborn,” says Arfin, “but ultimately, Judd has to remind me all the time that I haven’t been doing this for a thousand years like him.”

Once the narrative parameters were in place, Arfin did what she always does and began mining her own life for material. “Even though Mickey is sort of modeled on me, she’s a type of me that I like to think doesn’t exist anymore,” says the chatty Long Island native. “She’s very selfish.” Indeed, Arfin has outgrown her selfishness enough that she’s okay with watching her real-life husband act in a relationship with her fictional proxy. “What a turn-on!” she says. “I want people to love Paul as much as I do. Doesn’t mean there’s less of him for me.”

Prior to Love, Arfin had made her name as a writer with her revealing Vice column “

The thing that makes Love most different from the vehicles through which Arfin’s shared herself in the past is that now she’s got a room of co-writers. (She’d never seriously considered playing Mickey herself.) And all of them have been tasked with shaping the version of her that’s being presented. Which has its drawbacks. “I’m not crazy about being in a writers’ room,” admits Arfin, who, after leaving Girls, wrote for the Andy Samberg sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine. “I’ve had to say, ‘This is isn’t true to character,’ and when the writers don’t agree with me, I have to listen to them.” In this, her old boss’s efforts were instructive. “Girls is Lena’s show,” says Arfin. “She writes, directs, and stars. My voice in Love is a small percentage of it. There’s compromise.” Insight, too. Gillian Jacobs, for example, “tapped into a part of Mickey that I didn’t know existed — she’s smarter than she thinks. I never thought that about her.” She pauses. “I certainly never thought that about who I am before,” she says, then smiles, pleased at uncovering yet another part of herself.

Lesley Arfin Talks Love, On-Screen and Off | Vogue | February 19, 2016

There’s a scene in the trailer for the new Netflix series Love in which a guy (Gus, played by Paul Rust) rides shotgun in the car of a girl he just met (Mickey, played by Gillian Jacobs). Inspired by her freewheeling attitude and his own bitterness toward an ex-girlfriend, Gus disgustedly flings romantic comedy Blu-rays out the window.

“We just keep believing in this fucking lie that a relationship evolves and gets better,” he yelps as Mickey eggs him on. “Where do these lies come from? Fucking movies! Pretty Woman? Fuck you! Sweet Home Alabama? Lies! When Harry Met Sally? Fucking lies!”

It’s not the subtlest moment, but it pretty well sets the scene for the show, which bills itself as a rejoinder to the kind of pat, formulaic love stories depicted by the rom-com genre’s worst offenders.

In its 10-episode first season (a second is already in production), available on Netflix today, Love follows Gus, a nerdy tutor and aspiring screenwriter, and Mickey, a wild-child radio-show producer with a complicated relationship to substances, in their journey from total strangers to tentative romantic partners. But that arc is just a prelude to the show’s real undertaking: a darkly humorous look at a long-term relationship through all its peaks and troughs, with none of the typical Hollywood gloss.

Gus and Mickey seem at first like archetypes, but Love dives deep into their complex, often ugly psyches, to reveal them as far messier creatures than we might have imagined. When they come together, things get messier still, and the show’s narrative sometimes has a way of rambling. But since Love is really about process—about the stuttering momentum and miscommunications and uncertainty of a relationship—that untidiness ultimately works to bolster a sense of realism. And when the show begins slowly to peel back the layers of Mickey’s convoluted relationship to addiction, the commitment to realism really pays off.

Appropriately, the series comes from Judd Apatow, by now the industry’s go-to guy for projects that find the funny in romantic malaise. But the idea actually originated with the husband-wife team of Rust and writer Lesley Arfin (You know her from her long-ago “Dear Diary” column in Vice and her stint as a writer on Girls.) It reflects, Arfin tells me by phone, the questions she began asking herself as she and Rust settled in for the long haul. We chatted about her experience collaborating with her partner, the show’s unusual depiction of drug use, and why it’s important to see women behaving badly on-screen. That conversation, below.

Tell me about how this show happened.

Well, Paul is my husband, but he was my boyfriend at the time. He’s an actor and a writer, and I’m a writer, and his manager suggested that we write something together. I was like, “Ugh! Never! Worst idea!”

I had been writing a Web series that I was going to do with HBO called 34 and Pregnant, because I was 34 and I wasn’t pregnant and I wanted to be. So while I was working on this thing, I was like, I’ve never seen a movie that was about a relationship, but not a meet-cute and then a montage and then a happy ending. What happens when the honeymoon is over? What does a relationship looks like when you’re sitting on the couch in your sweats, eating ice cream, getting into fights, not having sex that much? I love Paul, but we’re not in our honeymoon phase. I was like: How do people stay in relationships? What does it look like? It’s this thing that everybody wants so badly, and at the end of the day we’re sitting on our couch eating ice cream and not having sex. What’s the big deal?

How long had you guys been together at that point?

Like three or four years. We both knew we wanted to marry each other. I had never felt that way about anybody. I’d been out with a lot of people.

Then I Googled the word love to see if it had ever been the title of a movie or a TV show. It hadn’t [at the time]. I talked to Paul about it. He was working with Judd at the time on Pee-wee’s Big Holiday. I’d known Judd from Girls. Judd said, “I love that idea, but I love it as a TV show if we start from the beginning and go through slowly from start to finish.”

I think Judd saw something in Paul and me as a couple. He and Paul are a lot alike. His wife, Leslie [Mann], and I are a lot alike. Paul’s the nerdy guy, and I’m the wild chick. But it’s not like I’m the Courtney Love and Paul’s the innocent Kurt Cobain. Paul has issues, too, and I’m a good person, too! We’re this odd couple that isn’t really that odd, that’s kind of every couple.

Was there any moment when you were thinking maybe this wasn’t a good idea?

Oh, my God, of course! Of course we fight. I don’t know if we were ever, like, maybe this is a bad idea, because it doesn’t affect us to that point. Nothing is more important to me than family and marriage. If the show were interfering with that, I would step away from the show first. It’s a TV show. Paul’s my husband. There are other TV shows.

He’s one of my favorite writing partners. But when we’re at work, when we’re in the same workspace, we bicker. There’s ego involved. He’s like, “Oh, Lesley, I don’t know about that idea,” and I’m like, “Stop feeling threatened!” It’s never about the work: We haven’t figured it out yet. There are other times when I think, What would I do if I didn’t have him at work? We really have each other’s back.

Has Judd offered any words of wisdom about collaborating with a spouse?

Totally. I was like, “Judd, how did you deal with watching Leslie and Paul Rudd have sex scenes?” He was like, “I think it’s the funniest thing. I love it; I think it’s hysterical.” Judd is very drama-free, so if there’s ever anything I’m freaking out about, he’s really helpful; he’s like, “It’s going to be fine; so much changes in editing.” I feel very safe with him.

You Instagrammed a quote recently from Maureen Dowd’s female filmmaker piece about Bachelorette

Yeah, as a writer and as a viewer. I’m interested in seeing women who make mistakes and, like, don’t learn a lesson from it. Or they make mistakes and the consequences aren’t that bad. Or maybe they make them again. Maybe there’s a way to have a female character who is both good and bad, and who isn’t a mom or a vixen or a baby.

I always think about Walter White and how he became the person he was meant to be, which was not a good person. Maybe he never was a good person. Maybe he was so afraid of being a bad person that when he was finally given permission by death, he was allowed the freedom to be himself. I really identify with that. I’m not selling meth. I’m not killing anybody; that’s not Mickey’s agenda. That’s not Gus’s agenda, but there’s something that Mickey does: She knows the difference between right and wrong, and sometimes she’ll make the wrong choice on purpose. Maybe the consequences for her aren’t so black and white. Maybe that’s the truth with Gus. I’m so sick of seeing the nerdy white boy as the hero to the crazy girl. I lived in that fantasy for so long, the Cinderella complex. I think Gus probably has that fantasy, too. I think he really loves the idea of being needed, being able to fix somebody. There’s a lot of anger behind that. I’d be less shocked if he sold meth.

There’s something I really get about fucking ruining your life on purpose.

Have you ever done that?

On purpose? Yes. Subconsciously? Yes. And accidentally? Yes.

I’ve had to make the same mistake eight times in a row before I realize: This isn’t going to work. There’s no moral lesson. It’s more of a behavioral thing, how to get along with the world, be at peace with myself and my decisions. But morally? I don’t know what that means. I’m not killing anybody and I’m not selling drugs. Anymore.

The relationship to drugs in the show is interesting. We see the characters doing lots of them, but it’s never quite clear to what extent they are a problem.

I don’t think that drugs are the problem. Alcoholism, addiction, those are diseases. Some people have that disease, some people don’t. You know what I love? I love in the movie Halloween, Jamie Lee Curtis smokes a joint and she’s the hero. Smoking a joint doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. It doesn’t mean you’re going to end up shooting heroin tomorrow. It’s important for me to show that. I’ve only ever seen: Drugs equals bad.

Although in Mickey’s case, she’s at least somewhat convinced that drugs are bad for her. Right?

And maybe for her they are. I think part of her journey is that drugs, booze, dude stuff—all that wasn’t helping her be happy at this moment. Maybe that’ll last. Maybe it won’t. But I also think she’s the person she is because of everything she’s done. She needed to experiment and figure out how to do things the wrong way before she knows what the right thing is for her.

Can you think of other characters like that, ones you related to?

I’ve always been inspired by Winona Ryder’s character, Veronica, in Heathers. There’s something very twisted, dark, wrong, and perfect about her. She shoots her fucking boyfriend at the end of the movie! I also loved Roseanne, how she never really apologized for who she was, and there were all sorts of problems going on in that family.

Carrie Bradshaw, too! What a great character. Somebody who just wanted to be in love so badly and was so obsessed with this guy who treated her like shit. But I get it! The whole series she suffered from it, but she wanted to suffer. I get the drama of wanting. I think that’s something about Mickey that I really relate to. It’s a part of me, too. We’re dramatic people. It doesn’t make you the most likable person. I don’t know if Carrie Bradshaw was the most likable person in the world, but people loved her because they related to her. She really was a female antihero.

Lesley Arfin Talks “Love” and Asking Lena Dunham for Advice | W Magazine | February 25, 2016

Love is an ideal Netflix show. Created by Judd Apatow, Lesley Arfin, and Paul Rust, the romance between Gus (Rust) and Mickey (Gillian Jacobs) burns so slowly that it may as well be happening in real time. But Arfin and Rust, who are married and who came up with the idea together (there is a lot of both in Mickey and Gus), are hoping that a series of small, honest, hilarious moments will, over time, add up to much more than your typical rom-com montage. (They’ll begin shooting a second season on Friday.) And Love is as lived-in and rumpled and embarrassing and charmingly messy as, well, love. Arfin, who was previously a writer on Girls (not to mention the editor of Missbehave), talked about her husband’s sex scenes and why it’s important to have haters after she binged the first season when it premiered over the weekend, just like the rest of us.

How are you? Do you have a feedback hangover from the weekend?

No! Not even. I’m so happy that people seem to like the show. But even if there’s backlash — my friend texted me the other day and she was like, ‘I’m overhearing people in the alleyway behind my house talk about Love.’

Is that the new subtweeting?

Talking about it in an alley? Yeah, that’s what the kids are calling it. It’s shorthand, but much longer. I was like, ‘What are they saying? Even if it’s bad, I don’t care.’ What would be worse is if nobody talked about it at all! I think if you don’t have haters, you’re doing it wrong!

The critics’ reviews, at least, are pretty positive.

Yeah, totally! And that’s awesome, too. I mean: that’s even better. [laughs] It’s cool when you make something, and people respond and identify with it. There’s nothing better. I do have like 30 unanswered texts.

They’ll understand.

I hope so! People are weird, and everybody wants everybody else to fail, or have a reason to hate somebody. I’m not a huge phone person anyway. So, whatever.

Funny that Love premiered the same weekend as the show you used to write on, Girls.

I consider them our sister show. Everybody there are still my closest friends. I ask Lena [Dunham] and Jenni [Konner] for advice all the time. Now I get to watch Girlsonce a week. And people can watch Love however they want.

I watched most of it while hungover.

That’s ideal. I watched every single one except the last one.

Why not the last one?

Because then it’s really over! Even though there’s another season. And especially watching it with Paul, there’s some stuff I never realized that just really hit so close to home for us. That is so meta.

So you two binged it together like everyone else?

We watched it together, alone, and with some friends who came over. But yeah, we just wanted to watch it on the big screen like the rest of the world. We’re proud of it. It’s kind of like when someone comes to your house for the first time, and you can see it through their eyes. Like: ‘Oh, I wonder what they think looks good or not?’

How did you feel about the pacing while watching it? It’s such a slow burn.

Part of our original idea for the show was we wanted to see what relationships were like when you cut into the montage. When you take that out, and you’re just in it. To do it as slowly and in real time as possible — it’s hard. I’ve never seen it before. As a person who’s in a relationship, I’m curious what that looks like. I’m interested in how unromantic it really is. I’m always interested in what’s beautiful about love, and what’s really ugly about it. We just wanted it to be a narrative out of a lot of small moments. Even if we didn’t have a two-season order from Netflix, that was always our approach. When we first had this idea, we wanted to do it as a movie. And when we told Judd about it, he was like, ‘I think it would be so great as a TV show.’ And he was right. He saw something we couldn’t see.

Have you gotten used to writing and being present for Paul’s sex scenes?

I think there was a time where I was like, ‘Um, should I be worried?’ And then I talked to Judd about it, who’s had a lot of experience with this [with his wife, actress Leslie Mann]. He was like, ‘Oh my god, it is the funniest thing, I love it.’

Paul’s character is an aspiring TV writer, but he’s not very good yet. There’s that awful scene on his one and only day in a writers’ room.

It’s so painful. Not that that doesn’t happen when I’m in the room on our show, but I’ve been in other writers’ rooms. No matter how many shows you’ve been on, when someone makes a joke in a writers’ room and no one laughs, a part of your soul dies. Especially with me — I’m not a natural collaborator when it comes to writing. Before I started working in TV, I just wrote on my own. The first time I got edited I was like, ‘Ugh. Oh my god.’ And now I’m like, ‘Thank god you’re making me sound like a better writer than I am.’ A great editor is kind of the same thing as a great showrunner.

You guys have stocked a lot of the secondary roles with comedians like Brett Gelman.

Some. But a lot of my friends who are just musicians or just natural performers are in there, too, like Binky Shapiro. I learned a lot about this from Judd. We didn’t want everybody to be so familiar, because then it gets to be a joke on a joke. Where it’s a show where a character like Gus is trying to make it in Hollywood, and all of these people who are well-known in Hollywood are pretending to be normal.

Some people have characterized Love as another show about awful people. While I don’t agree, does that upset you, knowing a lot of you and Paul are in these characters?

I think people are horrible. And I think people are beautiful. They’re both, all the time. This isn’t the story of the nerdy guy saving the crazy druggie girl. Everybody’s just trying to do their best; we just wanted to make it real.

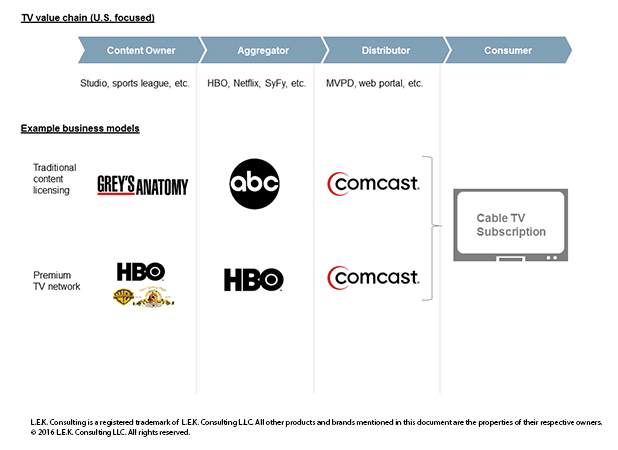

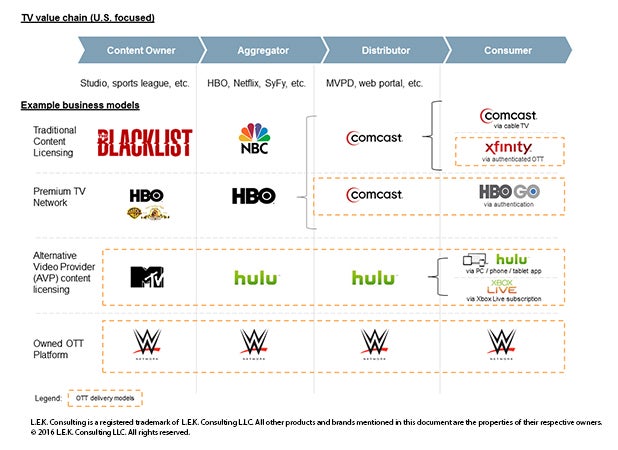

Although this seems to be a formidable model, OTT platforms are disintermediating the traditional TV network value chain, bringing content owners and consumers closer, and forcing the traditional players to compete in different ways. In today’s ecosystem, everything is new: new content creators, new aggregators, new distributors, new ways for consumers to access an ever-expanding portfolio of content. The next chart shows four distinct ways to think about OTT distribution:

Although this seems to be a formidable model, OTT platforms are disintermediating the traditional TV network value chain, bringing content owners and consumers closer, and forcing the traditional players to compete in different ways. In today’s ecosystem, everything is new: new content creators, new aggregators, new distributors, new ways for consumers to access an ever-expanding portfolio of content. The next chart shows four distinct ways to think about OTT distribution: Content owners, in particular, benefit from the development of OTT offerings. For example, they can establish relationships with consumers, obtain helpful feedback directly from consumers and wield greater control over how the content is shown and consumed.

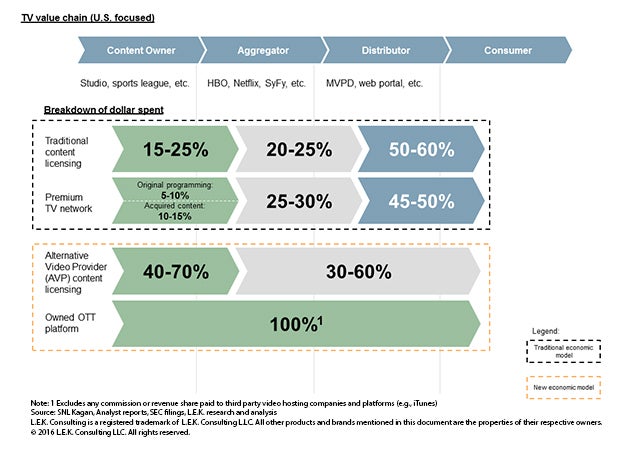

Content owners, in particular, benefit from the development of OTT offerings. For example, they can establish relationships with consumers, obtain helpful feedback directly from consumers and wield greater control over how the content is shown and consumed. Thus, in the traditional ecosystem, content owners only capture a fraction of what the consumer ultimately pays for their content as aggregators, and distributors take most of the cut. In the new value chain, content owners can boost their cut from the traditional 15-25 percent all the way up to 100 percent by going direct.

Thus, in the traditional ecosystem, content owners only capture a fraction of what the consumer ultimately pays for their content as aggregators, and distributors take most of the cut. In the new value chain, content owners can boost their cut from the traditional 15-25 percent all the way up to 100 percent by going direct.